Zora Neale Hurston, writer of the Harlem Renaissance and folklorist, was a unique individual. Born in 1891, she was raised in Eatonville, a free black town in north-central Florida. She is best known for her novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, which she wrote in the space of weeks inspired by the love of her life. From the time that her mother died when she was 13, Hurston was virtually on her own. What makes her so unique is her zest for life and her love of all things African American. She wrote in 1928 in "How It Feels To Be Colored Me": "I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. I do not mind at all. I do not belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all hurt about it.... No, I do not weep at the world, I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife."

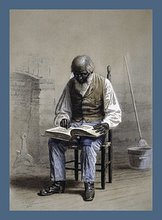

Hurston in the car she used for her touring in central areas of Florida

Her mission was to bring African Americans into the mainstream of American culture, but not by trying to blend but by discovering the stories and music with which African Americans entertained themselves and buoyed themselves up in the face of poverty, harsh work, and white hostility. "We have things to bring to the table" was her idea. She arrived in New York during a period in the 1920s when there was interest in African American culture and money to promote it. Unfortunately, the funding spigot was turned off during the depression of the 1930s and from what I can discern was never to be turned on again. Under the tutleage of anthropologist Franz Boas at Columbia University, Hurston (who never had a dime from her family for her education but depended upon grants, benefactors, and her wits) drove down to the Florida turpentine camps to dig out the music and stories of African Americans among the black workers and families there. She writes of her motivation: "Roll your eyes in ecstasy and ape his every move, but until we have placed something upon his street corner that is our own, we are right back where we were when they filed our iron collar off."

It took extraordinary bravery for a young woman on her own, without a man companion, to drive through the backwaters of Florida seeking stories and songs in the turpentine camps. But she did. Hurston in Eatonville, Florida, gathering songs

Hurston in Eatonville, Florida, gathering songs

I have recently come across the website of the Florida Memory Project, which has for free download, a collection of the songs that Hurston recorded for the WPA as part of her project of retrieving African American culture and bringing into wider view.

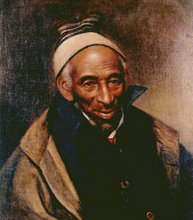

Hurston sponsored tours of African American dance troupes on a shoestring budget.

Hurston sponsored tours of African American dance troupes on a shoestring budget.

Zora Neale Hurston must have seen herself as an ambassador for African Americans into the white world. However, there was no bending, scraping, and shuffling. Her view was that African Americans had something unique to offer to American society; but if American society was so dumb as to reject it or ignore it, then that was their problem, and African Americans should be happy in their own company. Politically this put her in her later years in a strange position, since while African American intellectual leaders such as Richard Wright had all moved toward the left (Wright attacked her novels because they were not protest novels), she wound up in her later year as a conservative Republican even to the point of helping segregationist candidates.

Nevertheless she understood the obstacles facing African Americans, writing: "There is something about poverty that smells like death. Dead dreams dropping off the heart like leaves in a dry season and rotting around the feet; impulses smothered too long in the feted air of underground caves. The soul lives in a sickly air. People can be slave-ships in shoes."

But her own soul did not live in a sickly air.

In her later years, she moved back to Florida and settled in Fort Pierce on the Atlantic coast. There she taught at the Lincoln Academy and wrote for the local newspaper. She lived in a small house, kept a garden, used orange crates to hold her books, and in her last years was researching and writing a book on Herod.

Zora Neale Hurston's home at 1734 Avenue L in Fort Pierce, Florida

When she died at the age of 59 she was buried in the county cemetery in an unmarked grave. We owe a debt of gratitude to Alice Walker, who found Hurston's grave and placed a headstone on it and pioneered the revival of this wonderful woman's work. Fort Pierce now has markers for the places that were important for Hurston there, including her grave and home.

Zora Neale Hurston's gravesite, discovered by Alice Walker who also contributed the gravestone. The gravesite is at the Garden of Heavenly Rest Cemetery, Avenue S and 17th Street, Fort Pierce. The gravestone reads: ""A Genius of the South, 1901---1960 Novelist, Folklorist, Anthropologist"

Hurston's most famous work was her novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Alice Walker and others have praised it for what they consider its proto-feminist views--that is, the heroine of the novel is constantly unshackling herself from the bounds that society--in the first instance, her grandmother--have placed on her through one man or another. She falls in love with Teacake, a man younger than herself. Although Teacake dies, the heroine feels fully alive because of her total love for Teacake; the book is a celebration of this total love, which in its joy defies the poverty, difficulties, and racial barriers that the heroine faces. I took this as the message of the book--that the heroine finds her true self in totally loving another--rather than in fighting for herself strictly as a woman. To me, Hurston is flying in the face of the power of the matriarchy in African American society. In this, she stands in opposition to Toni Morrison as well as to Alice Walker. (Interestingly, Dorothy West, whose own mother exemplified this matriarchy as West describes it in her book Living Is Easy, was a close friend of Hurston's in Harlem.) That Hurston is celebrating the joys of loving the other is the interpretation that is in keeping with the work of Hurston's entire life. She did not apologize for being black, for being a woman, for being a human being, but sought to discover the rich lode of African Americans' iron grip on life and humanity and present it as a gift to America and to the world.

2 comments:

What a wonderful lady.

thanks for the article! great homage to a great lady... little appreciated in her own time.

Post a Comment