Walter Mosley's Walkin' the Dog is a continuation of the story of the 60-year-old Socrates Fortlow, the ec-convict who spent 27 years in jail for killing a friend and his friend's girlfriend, and has now been out of jail for 9 years, taking up his abode in a two-room shack in an alley in Watts. I listened to the book on CD, and the reading was highly differentiated and excellent. The first Fortlow story is Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned, which begins the exploration of Fortlow's attempts to find redemption for his crime through efforts that aid his community. This second Fortlow story is far more ambiguous in its plot, with the fight that Fortlow makes against his own rage and impulse to violence never an open and closed case, but a relentless fight. Provocations are plentiful.

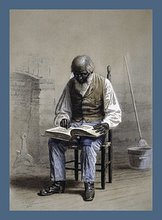

Mosley names Fortlow Socrates because he often asks his friends to help him examine pertinent questions, and he also is part of a discussion group that meets each week. Because Fortlow is himself such an engaging character and also because he is in a search for the truth, about himself and his place in the world, this book in particular offers a glimpse into the inner thoughts of a man such as he.

He is a man, for sure, but it is not easy for him to take responsibility--not for his crime, which he did and does--but responsibility in relationships. For example, he gets a job at the Bounty supermarket quite a ways a way, and he is very responsible in this job, starting at the bottom rung, and the manager finds him to be the most reliable worker he has and offers Fortlow the post of Produce Manager, which would mean a big increase in pay and responsibililty to oversee a department. Fortlow is extremely reluctant to take this position, constantly offering arguments why he should not--including the argument of "What about the white guys that I will be supervising? They won't like it." [paraphrase] The manager says he doesn't care about that. Fortlow does take the job and does well, which would be expected.

He is also reluctant to take up the offer from Iula, who owns his favorite diner, that he combine with her and be her right-hand man in the diner. She wants to marry him, but he will not do this. She then goes back, briefly, with her former husband, and after they part, Fortlow takes her as his girlfriend, and they see each other on the weekends. Although Fortlow undoubtedly cares in some way and she certainly cares for him, it does not seem that he in any way emotionally gives up his fundamental independence or opens himself up to her in this relationship.

He takes moral responsibility for Darryl, the young boy he rescued in the first novel, although not physical responsibility for him. He teaches Darryl and also trusts Darryl completely. They confess to each other. It is through his relationship to Darryl that his aspirations for himself, both outwardly and inwardly, are mirrored for him.

Fortlow's major goals seem to be to defend his independence as a man against all forms of assault, from a mugger, from the police (who harass him constantly since he is an ex-con), from different kinds of women. He necessarily stands against hand-outs; he is reluctant to furnish his new apartment--"... his house was bare and pristine. He walked around the rooms smiling. He had a home that he loved but still he could disappear leaving nothing behind."

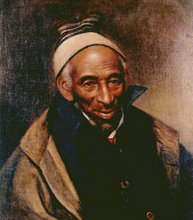

Socrates is trying to deal with his own anger, his own compulsion to violence. This is a physical feeling in him, like coming up his back and his neck into his hands, when it arises. At one point in his relations with the harassing cops, one of them is waiting for him at his gate when he gets home. The cop asks him where he has been, and Socrates answers,

"Nowhere, I ain't been nowhere. And I sure am tired so if you wanna arrest me please do it or let me pass." "Why would I want to arrest you, Socrates? Have you done something wrong?" Thats when Socrates realized that some time in the last week the violence had drained out of his hands. He didn't want to hurt anybody. He didn't care that Biggers [the cop] stood there in that silly suit trying to act like he was going to trick Socrates into a confession. A confession to anything. "Let me pass, man," was all Socrates had to say.

Later in the book, in his discussion group, Socrates poses this question: "What I wanna know is if you think that black people have a right to be mad at white folks or are we all just fulla shit an' don't have no excuse for the misery down here an' everywhere else?"

He then tells a story his aunt Bellandra had told him about a slave uprising in which the slaves kill the master and burn down the plantation and then head into the cane, from which they maraude other plantations but they can never leave the cane. The story is the answer to the question, the group says. "I'm not sure," Socrates said. "I mean I been thinkin' about bein' mad at white folks lately. I mean I'm always mad. But bein' mad don't help. Even if I say somethin' or get into a fight, I'm still mad when it's all over. One day I realized that I couldn't stop bein' mad. Bein' mad was like havin' an extra finger. I don't like it, everybody always make fun of it, but I cain't get rid of it. It's mine just like my blood." ... "Why did you ask the question?" Chip Lowe asked. "Because I'm tired of bein' mad, man. Tired. I see all these white people walkin' 'round and I'm pissed off just that they're there. And they don't care. They ain't worried. They thinkin' 'bout what they saw on TV last night. They thinkin' about some joke they heard. An' here I am 'bout to bust a gut."

Then, after everyone leaves, and he looks around the room and at his folding chairs and thinks of his friends who had been in in them [the group met at his house this night]. "He thought about being angry himself. Somewhere in the night he realized that it wasn't just white people that made him mad. He would be upset even if there weren't any white people."

Then in the last episode of the book, Fortlow decides to take matters into his own hands concerning a policeman who was known to mercilessly harass blacks and who had gunned down a teenage black boy for no reason at all. He bought guns and ammunition and prepared to kill the white cop, and stalked him for that purpose. "The murder in the air came in through his lungs and from there to his blood. Socrates, who knew that he had been prepared for centuries, was finally ready to answer a destiny older than the oldest man in the world. Cardwell [the cop] obliged and walked toward the dark alley. He was smoking a cigarette, moving at an unhurried pace. He was thinking about something. Socrates breathed deeply and tasted the air. It filled him with a sweetness of anticipation that he had not felt since the first time a woman, Netalie Brian, had helped him find his manhood.

'It was the air, no, no, no, the breath of air,' Socrates told Darryl the next morning on the phone. 'It was so good. I mean good, man. You know I almost called out loud. I saw Cardwell walkin' my way an' my hands was tight on them guns. You know he was a dead man an' didn't know it. .... But I was gonna murder that man. I was gonna kill him. But I was thinkin' that I had never felt nuthin' like that deep breath I just took. An' eve though I was gettin' ready to kill I had to take just one second to think about how I felt. You know?' ' I guess I do,' Darryl said. ' But how did you feel?' 'I felt free, ' Socrates said in a soft voice. 'All my life I ain't never felt like that. I was ready to die along with that man. My life for his--you cain't get more free than that." 'Did you kill him?' Darryl whispered the question... 'I meant to. The guns was out and he passed not three feet from me. But I just stood there--smiling, thinkin' 'bout how good it felt to be in my own skin.'"

Now this is a different kind of outcome than that prescribed by Frantz Fanon. According to Fanon, Fortlow could only have become free and found his own sense of identity by killing the cop. Instead, something about the air--or the air as encapsulating his talks with his friends and his relationship to Darryl and to Iulia and to others that he had been steadily building over the course of the two books--something in the air about his own reconciliation with others and with himself, made him choose life.

But he did not stop fighting. He then got a poster made listing Cardwell's crimes and picketed the police headquarters. This caused provocations on their side and then people gathered round to defend Fortlow from arrest and then there was violence by others, etc., teargas, etc., and Socrates in the news and famous with his billboard. He was jailed for 3 days and lost his job. He had no illusions that his act had fundamentally changed anything, but he felt good afterward and stayed in LA, it is implied, to continue his acts of self-redemption, to build his life with them.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment