Right off, we can tell from the title that Elkins believes that slavery and its aftermath pose a problem for all Americans that, if it had already been solved, would not necessitate his writing the book. This is important, because to my mind Elkins begins to get at the problem that Ralph Ellison points to, that slavery, Jim Crow, and the continuing crisis in race relations have fostered a "culture that is opposed to the deep thought and feeling necessary to profound art; hence its avoidance of emotion, its fear of ideas, its obsession with mere physical violence and pain, its overemphasis of understatement, its precise and complex verbal contructions for converting goatsong into carefully undulated squeaks." [See "Assumptions to be Tested" in January Archives]

The crucial point is made in the second essay, in the comparison of the slave systems of the United States and of South America. Brazil's slave system was closer to that of the United States, but in his rejoinder to critics on this score, Elkins documents that the differences that still remained were crucial in the Brazilian case also. Elkins makes this a polemic about institutions or the lack thereof in the United States. There were no institutions in the United States, he says, to put a brake on the rapaciousness of the Southern planters, whereas in South America there were. Elkins in part wants to shift the historiographic debate from a moral debate on slavery--pro and con--to an examination of the wider cultural and legal context for the chattel system of slavery that existed here, which he says, is unprecedented in history. Inadvertently perhaps, however, he begins to get to the crux of the problem in the United States that continues to plague us today.

Elkins does not compare the conditions of slaves here and in South America per se but compares the legal structures that held the slave systems in place. For the United States, he presents an overview of the transition in colonial America, from a situation in which there were many indentured servants, both white and black, to the elevation of the white indentured servants and the full-scale enchattelment of the black indentured servants and new slaves, and its corollary, the de-elevation of free blacks to the status of second-class citizen. By 1710 the flow of white servants to America had virtually come to a halt [49]. "For the plantation to operate efficiently and profitably, and with a force of laborers all of whom may have been fully broken to plantation discipline, the necessity of training them to work long hours and to give unquestioning obedience to their masters and overseers superseded every other consideration. The master must have absolute power over the slave's body, and the law was developing in such a way as to give it to him at every crucial point. Physical discipline was made virtually unlimited and the slave's chattel status unalterably fixed."

This was the slave's fixed legal status. This legal status had been established by the latter half of the seventeenth century. Elkins then examines three other aspects of the slaves' legal status:

marriage and family; police and disciplinary powers over the slave; and property and other civil rights.

For the slave in the United States, "That most ancient and intimate of institutional arrangements, marriage and the family, had long since been destroyed by the law, and the law never showed any inclination to rehabilitate it." Although informally masters may have permitted marriage, and although the slavetrader who separated familes was viewed with contempt in white society, nevertheless, "yet the very nature of the plantation economy and the way in which the basic arrangements of Southern life radiated from it, made it inconceivable that the law should tolerate any ambiguity, should the painful clash between humanity and property interest ever occur." Elkins also notes that children derived their condition from their mother, since if it were conferred by the father's condition, the question would be what to do with all the mulatto children born of slave mothers and white masters? "That 'the father of a slave is unknown to our law' was the universal understanding of Southern jurists. It was thus that a father, among slaves, was legally 'unknown,' a husband without the rights of his bed, the state of marriage defined as 'only that concubinage...with which alone, perhaps their condition is compatible.'"

In matters of discipline, the slave had no repeal and no recourse, no standing before the law. There was never any law upholding the slave's rights against assault, and therefore no law was violated if a master did what he would with a slave, even up to the point of murder. (Of course this lawlessness outlasted slavery, as can be seen from the post-Civil War lynchings and disappearances of African American men, and even in boys, as shown by the murder of Emmett Till.)

The rights of property, and all other civil and legal rights were "everywhere denied the slave with a clarity that left no doubt of his utter dependency upon his master. 'A slave is in absolute bondage; he has no civil right; and can hold no property, except at the will and pleasure of his master." He could make no gifts, write no will, inherit nothing. He did not own himself, as he could not hire himself out or make contracts for any purpose. "Neither his word nor his bond had any standing in law." In delineating this, Elkins quotes from Alabama court opinions.

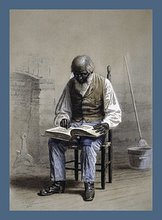

The slave had no civic privileges of religion or education. With the exception of Maryland and Kentucky, he reports, stringent laws were in place prohibiting anyone from teaching a slave to read or write. In North Carolina it was against the law to give a slave any book, including the Bible. Slaves were only allowed to worship within the carefully constructed constraints set by white preachers and the master. They were forbidden to worship outside of those bounds--if at all, and hence the spiritual, Steal Away. Although the Presbyterian Church had deplored this condition, the churches were unable or unwilling to do anything about it.

This created the "most unplacable race-consciousness yet observed in virtually any society." The syllogism went like this: "All slaves are black; slaves are degraded and contemptible; therefore all blacks are degraded and contemptible." This racial hysteria of the South precluded the concept a free black; "such a class was unnatural, logically awry, a blemish on the body politc, an anomaly for which there was no intellectual category."

Elkins contrasts this North American institution of chattel slavery with slavery in the Ibero-dominated South America, noting first that slavery had existed in Spain for centuries, before the arrival in the 15th century of slaves from Africa. Thus a slave system existed that had two contradictory assumptions: slavery existed, but slavery was a violation of man's divine and natural equality and "against reason and nature." Thus the slave system was a bundle of laws that treated the slaves as persons who had gotten into a bad strait and had lost rights, but with avenues available to re-acquire those natural rights, as opposed to persons who had no inherent personhood or rights. Elkins says that this difference exists, because the Ibero slavery was far closer to the slave systems of antiquity, and also because the semi-medieval character of Spain placed institutional constraints on the capitalist planters: the crown and the church.

For the crown, "the introduction of slaves into the colonies brought much discomfort to the royal conscience." Charles V, who had first granted license to transport large numbers of blacks from Africa to the colonies, ordered the freeing of all slaves in South America, but when he retired to the monastery this was overturned. Same with Queen Isabella earlier. King in 1679 was looking for theologians who had written on the subject of slavery. From this it followed, that legally the slavemaster never had the total control over the slave's body that characterized slavery in North America. A master could legally beat a slave, but not to the point of drawing blood or inflicting contusions. If a slave was accused of crimes, he was tried in the same court that any free man would be tried in. Slaves had legal holidays and legally mandated time off. Slaves could buy their freedom, by contracting their labor out to another person. The master was legally forced to set a sales price. These laws were generally enforced, except in Brazil where enforcement was weak.

As for the church, while it did acknowledge slavery and accommodate to it, it nonetheless also consistently warned that the slaveholder was in danger of mortal sin. Hence, the church was active in encouraging slave manumission, which was permitted throughout the system. The church never denied the injustice of slavery, and the 18th-century prelate Cardinal Gerdil stated categorically: "Slavery is not to be understood as conferring on one man the same power over another that men have over cattle...For slavery does not abolish the natural equality of man."

Thus, the church acted to encourage manumission to save the mortal soul of the slaveower and also acted to better the conditions of those in slavery. The church ministered to slaves. This means that slaves had to be baptized and to take the sacraments, including the sacrament of marriage. Slaves owned by different owners who wanted to marry were to be allowed to do so; families could not be separated. The church ministered to slaves and also priests functioned as inspectors of the system, reporting cases of abuse, etc. " As Elkins reports:

"A Caribbean synod of 1622, whose santiones had the force of law, made lengthy provisions for the chastisement of masters on feast days. Here the power of the Faith was such that master and slave stood equally humble before it. 'Every one who has slaves,' according to the first item in the Spanish code, 'is obliged to instruct them in the principles of the Roman Catholic religion and the necessary truths in order that the slaves may be baptized within the first year of their residence in the Spanish dominions.' Certain assumptions were implied therein which made it impossible that the slave in this culture should ever quite be considered as mere property, either in law or in society's customary habits of mind. These assumptions, prepetuated and fostered by the church, made all the difference in his treatment by society and its institutions, not only while a slave, but also if and when he should cease to be one. They were, in effect, that he was a man, that he had a soul as precious as any other man's, that he had a moral nature, that he was not only as susceptible to sin, but also as eligible for grace as his master--that master and slave were brothers in Christ." [emphasis added]

It was precisely this status as a man under God that was denied to the slave of the South and also to the freed Negro. The heart of the chattel slavery and Jim Crow society in the United States is the denial of the soul of the African American. Witness the syllogism Elkins states above. This denial of a soul is at the root of the sickness in America in race relations. For how can anyone deny the soul of another human being, without also incurring grave damage to their own? Is this the source of what Ellison calls "the culture that is opposed to the deep thought and feeling necessary to profound art"? This is the avenue for exploration. Nor should it be thought that this existed only in the South, witness the virulent and violent reactions when blacks attempt to move into white Northern neighborhoods.

Even worse, the slave and black person was not only denied a soul but positively demonized, in order to perpetuate a rationale for the existence of slavery and Jim Crow itself. Hence, the struggle for civil rights and racial justice in the United States has always take the form of an assertion of soul: its emergence from the African American churches; the eloquent expression of this soul through at first religious music; the Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. DuBois, and then later: soul food, soul music, soul brother. Talk of soul food, soul music, soul brother would never be necessary in a society in which the soul of an African American were taken for granted.

In South America, because the slave and the black was never denied a soul, they could be freely assimilated into the society. The society's racism was in the form of a caste system, so that a wealthy black person was fully assimilated and considered "white." Writes Elkins: "Free Negroes had the same rights before the law as whites, and it was possible for the most energetic of their numbers to take immediate part in public and professional life."

Elkins concludes: "All such rights and opportunities existed before the abolition of slavery; and thus we may note it as no paradox that emancipation, when it finally did take place, was brought about in all these Latin American countries 'without violence, without bloodshed, and without civil war.'" [Elkins quoting Tannenbaum, Slave and Citizen]

The continuing lack of assimilation of African Americans into American society, it therefore follows, represents the continuation of the denial of the soul to the African American, now in the context of a society in which many deny the existence of the soul at all.

Sunday, March 19, 2006

Friday, March 10, 2006

Hats Off to Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

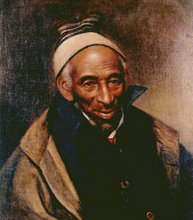

I first came across the name of Henry Louis Gates, Jr., in reference to Africa, because he stirred up a hornet's nest of controversy over his charge that African chiefs were responsible for slavery because they had sold captive Africans to the slave traders. This is obviously a bowdlerization of what he said, but what he did say created a bitter conflict among leading Africans and African Americans engaged in African-African-American studies. I disagreed with Gates at the time. However, on the same trip that he made this "discovery," he also salvaged manuscripts from Timbuktoo, and just this kind of digging is so sorely needed for the effort to discover the truth about African and African American history and also made it clear that Gates loved Africa.

Now, with his PBS special for Black History month, African American Lives, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has made a tremendous contribution to all Americans: he has discovered a way to trace African American roots backwards in time in the United States and all the way back to Africa. Gates took a number of stellar personalities among African Americans, including Whoopi Goldberg, Oprah Winfrey, Ben Carson, Quincy Jones, himself, and others and through painstaking digging in archives ferreted out the family tree of these well-known African Americans and then, on camera, presented these celebrities with the results. Most people had no idea of who their ancestors were or what they had done. Gates himself tried to find out how his great-grandmother had a house all her own in West Virginia after the Civil War, and did a DNA test on various relatives and a prominent local white family to determine if his grandmother's descendants had the same DNA as the man she worked for (which the family had for years assumed), only to find out that they did not! So the white man behind his ancestor's house and mulatto children remains a mystery man.

In each case in which Gates showed these stellar figures about their ancestors, they were deeply moved. They were filled; something that was heretofore hollow in them was filled. In some cases, they learned about white ancestors, slave owners. Or they learned how their family had hosted the black school in their district after the official black school was arsoned. Or they learned about how hard their ancestors had worked to get property and keep it. Or they learned how an ancestor who was a minister had refused to go north so that he could continue to lead his flock in the south.

In Part II of this series, Gates went even further. He recruited DNA experts to trace the DNA of these celebrities to their African roots. This is a contribution both of modern technology and Gates' heart. A white American may have lost sight of any ancestors who were not born in this country, but this is not really a problem for that white American, because he or she thinks of themselves totally as being an American. There is nothing in them held back to that commitment. But what if you are denied that identity as an American, as African Americans are? Then it becomes very important to know who you are. This knowledge is denied African Americans, who need that knowledge the most. As one African American friend of mine replied to an African who asked him, Where are you from?: "I don't really know." They both laughed, but it was a sad laugh for the African American.

With a DNA printout of peoples from all over the world, Gates and his DNA experts were able to isolate that part of the DNA that is passed on and on through generations and to match that with DNA types from various areas of Africa and to show the celebrities exactly from which area they had come from in Africa. In the case of Chris the comedian (I don't remember his full name), they then flew him to Angola to meet his tribe, who had been defeated in a war with the Portuguese and sold into slavery, and there was much rejoicing within this community in welcoming Chris back home.

After discovering where she came from, Whoopi Goldberg said, "This is my country. My country tis of thee." Maybe she meant Africa, but maybe she also meant the United States, because now she felt that she could hold her head high and belong.

Because they now knew where they came from, these African Americans could feel more truly American, because they no longer had to feel ashamed that they did not know where they came from. This is a tremendous contribution to the African American community in the United States and therefore to all Americans. If I were a Bill Gates, I would put up the money to enable every African American to know where they came from.

And what else might we find? In Gates' own family, he expected his mother's line at to least trace back directly back to Africa, but it traced to places like Dublin! Of course there was a lot of intermarriage between Irish and African Americans in the 19th century in the north. The DNA experts did manage to isolate Gates' African strain, I think tracing it back to areas of Nigeria. How many whites, we might ask, may be shown to have African blood?

Henry Louis Gates is a historian impassioned with the love of his people--and that love has borne nourishing fruit.

Now, with his PBS special for Black History month, African American Lives, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has made a tremendous contribution to all Americans: he has discovered a way to trace African American roots backwards in time in the United States and all the way back to Africa. Gates took a number of stellar personalities among African Americans, including Whoopi Goldberg, Oprah Winfrey, Ben Carson, Quincy Jones, himself, and others and through painstaking digging in archives ferreted out the family tree of these well-known African Americans and then, on camera, presented these celebrities with the results. Most people had no idea of who their ancestors were or what they had done. Gates himself tried to find out how his great-grandmother had a house all her own in West Virginia after the Civil War, and did a DNA test on various relatives and a prominent local white family to determine if his grandmother's descendants had the same DNA as the man she worked for (which the family had for years assumed), only to find out that they did not! So the white man behind his ancestor's house and mulatto children remains a mystery man.

In each case in which Gates showed these stellar figures about their ancestors, they were deeply moved. They were filled; something that was heretofore hollow in them was filled. In some cases, they learned about white ancestors, slave owners. Or they learned how their family had hosted the black school in their district after the official black school was arsoned. Or they learned about how hard their ancestors had worked to get property and keep it. Or they learned how an ancestor who was a minister had refused to go north so that he could continue to lead his flock in the south.

In Part II of this series, Gates went even further. He recruited DNA experts to trace the DNA of these celebrities to their African roots. This is a contribution both of modern technology and Gates' heart. A white American may have lost sight of any ancestors who were not born in this country, but this is not really a problem for that white American, because he or she thinks of themselves totally as being an American. There is nothing in them held back to that commitment. But what if you are denied that identity as an American, as African Americans are? Then it becomes very important to know who you are. This knowledge is denied African Americans, who need that knowledge the most. As one African American friend of mine replied to an African who asked him, Where are you from?: "I don't really know." They both laughed, but it was a sad laugh for the African American.

With a DNA printout of peoples from all over the world, Gates and his DNA experts were able to isolate that part of the DNA that is passed on and on through generations and to match that with DNA types from various areas of Africa and to show the celebrities exactly from which area they had come from in Africa. In the case of Chris the comedian (I don't remember his full name), they then flew him to Angola to meet his tribe, who had been defeated in a war with the Portuguese and sold into slavery, and there was much rejoicing within this community in welcoming Chris back home.

After discovering where she came from, Whoopi Goldberg said, "This is my country. My country tis of thee." Maybe she meant Africa, but maybe she also meant the United States, because now she felt that she could hold her head high and belong.

Because they now knew where they came from, these African Americans could feel more truly American, because they no longer had to feel ashamed that they did not know where they came from. This is a tremendous contribution to the African American community in the United States and therefore to all Americans. If I were a Bill Gates, I would put up the money to enable every African American to know where they came from.

And what else might we find? In Gates' own family, he expected his mother's line at to least trace back directly back to Africa, but it traced to places like Dublin! Of course there was a lot of intermarriage between Irish and African Americans in the 19th century in the north. The DNA experts did manage to isolate Gates' African strain, I think tracing it back to areas of Nigeria. How many whites, we might ask, may be shown to have African blood?

Henry Louis Gates is a historian impassioned with the love of his people--and that love has borne nourishing fruit.

Monday, March 06, 2006

On Stanley Elkins' Slavery: The Sambo Thesis

The full title of Stanley M. Elkins' book, published first in 1959, is Slavery: A Problem in American Institutional and Intellectual Life. Elkins is right: Slavery was and continues to be a problem in American institutional and intellectual life. This is the great contribution of the book. The book comprises four essays: 1. an overview of the American historiography of slavery; 2. a comparison of the U.S. and South American slave systems; 3. a comparison of the African American stereotype with the personalities that emerged among survivors in German concentration camps; and 4. a critique of the Abolitionists and Transcendalists, such as William Lloyd Garrison and Ralph Waldo Emerson et al., whom he calls intellectuals without responsibility.

The book caused an uproar because of the third essay primarily and also because it was known that Elkins had been influential on Daniel P. Moynihan; castigation of Elkins for the third essay and the rejection of the Moynihan report by black civil rights leaders went hand in hand.

Elkins' comparison of the black stereotype, which he calls Sambo, with the emergent infantilism among survivors in German concentration camps comes from some kind of musings, that if Elkins had followed through with more rigor might have led to insights. However, in its raw form as presented in the book, it is just wrong, and Elkins admits this in the later essays he wrote (which appear in the edition I read). There is no reason to compare a stereotype with the documented personalities that emerged among survivors in concentration camps. The first is a stereotype and therefore reified according to the interests and prejudices of the formulators of the stereotype. There were available to Elkins at the time the writings of Ralph Ellison (named after Ralph Waldo Emerson in fact) and also of Zora Neale Hurston, among others, from which he could have attained a far more accurate view of the personalities of those Americans who emerged from slavery. The actual African American both during slavery and after slavery is far more complicated than the simple image of "Sambo" and far richer. It is unfortunate that Elkins included this half-serious comparison in his book, because the contribution of the book is his analysis not of African Americans but of white Americans and American institutions. Perhaps whites therefore were also at the time just as happy to see Elkins under fire.

In the book, The Over Slavery: Stanley Elkins' and His Critics, the most moving answer to Elkins comes from Sterling Stuckey in his "Through the Prism of Folklore: The Black Ethos in Slavery." An African American professor, now retired, Stuckey writes: "What is at issue is at issue is not whether American slavery was harmful to slaves, but whether, in their struggle to control self-lacerating tendencies, the scales were tipped toward a despair so consuming that most slaves, in time, became reduced to the level of Sambos.

"My thesis, which rests on an examination of folk songs and tales, is that slaves were able to fashion a life style and set of values--an ethos--which prevented them from being imprisoned altogether by the definitions which the larger society sought to impose." This ethos, "an amalgam of Africanisms and New World elements" helped the slaves to endure. "The process of dehumanization was not nearly as pervasive as Stanley Elkins would have us believe; that a ver large number of slaves, guided by this ethos, were able to maintain their essential humanity." After giving many examples of spirituals, Stuckey notes: "For if they did not regard themselves as the equals of whites in many ways, their folklore indicates that the generality of the slaves must have at least felt superior to whites morally. .... There is some evidence that slaves were aware of the special talent which they brought to music. Higginson has described how reluctantly they sang from hymnals--'even on Sunday'--and how 'gladly' they yielded 'to the more potent excitement of their own spirituals.'... What is of pivotal import, however, is that the esthetic realm was the one area in which slaves knew they were not inferior to whites. Small wonder that they borrowed many songs from the larger community, then quickly invested them with their own economy of statement and power of imagery rather than yield to the temptation of merely repeating what they had heard. Since they were essentially group rather than solo performances, the values inherent in and given affirmation by the music served to strengthen bondsmen in a way that solo music could not have done."

The work that remains to be done, says Stuckey, is discovering the contributions of slaves to American culture. This is what Zora Neale Hurston had tried to do. See

http://ctl.du.edu/spirituals/ for a wonderful history (with many audio clips) of the spiritual. The media clips confirms Stuckey's discussion.

The book caused an uproar because of the third essay primarily and also because it was known that Elkins had been influential on Daniel P. Moynihan; castigation of Elkins for the third essay and the rejection of the Moynihan report by black civil rights leaders went hand in hand.

Elkins' comparison of the black stereotype, which he calls Sambo, with the emergent infantilism among survivors in German concentration camps comes from some kind of musings, that if Elkins had followed through with more rigor might have led to insights. However, in its raw form as presented in the book, it is just wrong, and Elkins admits this in the later essays he wrote (which appear in the edition I read). There is no reason to compare a stereotype with the documented personalities that emerged among survivors in concentration camps. The first is a stereotype and therefore reified according to the interests and prejudices of the formulators of the stereotype. There were available to Elkins at the time the writings of Ralph Ellison (named after Ralph Waldo Emerson in fact) and also of Zora Neale Hurston, among others, from which he could have attained a far more accurate view of the personalities of those Americans who emerged from slavery. The actual African American both during slavery and after slavery is far more complicated than the simple image of "Sambo" and far richer. It is unfortunate that Elkins included this half-serious comparison in his book, because the contribution of the book is his analysis not of African Americans but of white Americans and American institutions. Perhaps whites therefore were also at the time just as happy to see Elkins under fire.

In the book, The Over Slavery: Stanley Elkins' and His Critics, the most moving answer to Elkins comes from Sterling Stuckey in his "Through the Prism of Folklore: The Black Ethos in Slavery." An African American professor, now retired, Stuckey writes: "What is at issue is at issue is not whether American slavery was harmful to slaves, but whether, in their struggle to control self-lacerating tendencies, the scales were tipped toward a despair so consuming that most slaves, in time, became reduced to the level of Sambos.

"My thesis, which rests on an examination of folk songs and tales, is that slaves were able to fashion a life style and set of values--an ethos--which prevented them from being imprisoned altogether by the definitions which the larger society sought to impose." This ethos, "an amalgam of Africanisms and New World elements" helped the slaves to endure. "The process of dehumanization was not nearly as pervasive as Stanley Elkins would have us believe; that a ver large number of slaves, guided by this ethos, were able to maintain their essential humanity." After giving many examples of spirituals, Stuckey notes: "For if they did not regard themselves as the equals of whites in many ways, their folklore indicates that the generality of the slaves must have at least felt superior to whites morally. .... There is some evidence that slaves were aware of the special talent which they brought to music. Higginson has described how reluctantly they sang from hymnals--'even on Sunday'--and how 'gladly' they yielded 'to the more potent excitement of their own spirituals.'... What is of pivotal import, however, is that the esthetic realm was the one area in which slaves knew they were not inferior to whites. Small wonder that they borrowed many songs from the larger community, then quickly invested them with their own economy of statement and power of imagery rather than yield to the temptation of merely repeating what they had heard. Since they were essentially group rather than solo performances, the values inherent in and given affirmation by the music served to strengthen bondsmen in a way that solo music could not have done."

The work that remains to be done, says Stuckey, is discovering the contributions of slaves to American culture. This is what Zora Neale Hurston had tried to do. See

http://ctl.du.edu/spirituals/ for a wonderful history (with many audio clips) of the spiritual. The media clips confirms Stuckey's discussion.

Other Books Read

I have read the following books since the last post on Martin Luther King:

Rituals of Blood: Consequences of Slavery in Two American Centuries, by Orlando Patterson

The Debate Over Slavery: Stanley Elkins and His Critics, Ann J. Lane, ed.

The Moynihan Report: National Call to Action

Little Scarlet by Walter Mosley

Walkin' the Dog by Walter Mosley

Freedom's Daughters: The Unsung Heroines of the Civil Rights Movement from 1830 to 1970 by Lynne Olson

Ella Baker: Freedom Bound by Joanna Grant

Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision, by Barbara Ransby(very well researched; not yet finished)

Slavery by Stanley Elkins

Lay My Burden Down:Unraveling Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis Among African-Americans by Alvin F. Poussaint, M.D., and Amy Alexander

Rituals of Blood: Consequences of Slavery in Two American Centuries, by Orlando Patterson

The Debate Over Slavery: Stanley Elkins and His Critics, Ann J. Lane, ed.

The Moynihan Report: National Call to Action

Little Scarlet by Walter Mosley

Walkin' the Dog by Walter Mosley

Freedom's Daughters: The Unsung Heroines of the Civil Rights Movement from 1830 to 1970 by Lynne Olson

Ella Baker: Freedom Bound by Joanna Grant

Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision, by Barbara Ransby(very well researched; not yet finished)

Slavery by Stanley Elkins

Lay My Burden Down:Unraveling Suicide and the Mental Health Crisis Among African-Americans by Alvin F. Poussaint, M.D., and Amy Alexander

Sunday, March 05, 2006

One-Third of All Abortions in the U.S. Are of African American Babies

Abortion and African-Americans Interview With Alveda King, of Priests for Life NEW YORK, MARCH 3, 2006 (Zenit.org).- Every aborted baby is like a slave in the womb, in that the mother decides the little one's fate, says the director of African-American outreach for Priests for Life. Alveda King, niece of slain civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., advocates righteous living as the only way to solve the problem of abortion. ZENIT interviewed Alveda King about the effects of abortion particularly on the black population in the United States. Q: Statistics seem to show that abortion is aimed at specific groups such as African-Americans, immigrants and the poor. How do you see the situation? King: Abortion is a deadly genocide for all populations. Yet, evidence shows that groups such as Planned Parenthood have targeted African-American communities with a campaign to encourage young black parents to abort babies. Q: What is the stance of groups such as Planned Parenthood toward minorities? Do these groups do anything besides providing abortion? King: In the African-American communities, abortion is the primary agenda. They also offer birth control and some health services, but the emphasis is on abortion for black parents. Q: There is a high abortion rate among African-Americans and it reflects a problem with unwed mothers that needs to be solved. Abortion seems to deal with the "symptom" of children as if this were the solution. What is the proper solution? King: The proper solution is righteousness and holy living, including abstinence and marriage. This is the case for all people, regardless of nationality and socioeconomic status. Q: How has abortion affected the African-American family in the United States since 1973, the year abortion was legalized across the board? King: Of the estimated 45 million abortions performed in the U.S. since 1973, approximately 15 million are reported to have been in African-American families. Q: You said recently, "How can the dream survive if we murder the children?" Could you elaborate? King: In the ongoing travesty of the debate over whether abortion and infanticide should be condoned, a voice in the wilderness continues to cry out, "What about the children?" We have been fueled by the fire of "women's rights" [for] so long that we have become deaf to the outcry of the real victims whose rights are being trampled upon: the babies and the mothers. Of course a woman has a legal right to decide what to do with her own body. Yet, she also has a right to know the serious consequences and repercussions of making a decision to abort her child. Then too, what about the rights of each baby who is artificially breached before coming to term in his or her mother's womb, only to have her skull punctured, and feel -- yes, agonizingly feel -- the life run out of her before she takes her first breath of freedom. What about of the rights of these women who have been called to pioneer the new frontiers of the new millennium only to have their lives snuffed out before the calendar even turns? What terribly mixed signals we are sending to our society today? We allow and even encourage them to engage in promiscuous sex. Then when their sin conceives, we pretty much tell them, "Don't kill your babies, let our abortion facilities do it for you." My grandfather, Dr. Martin Luther King Sr., once said, "No one is going to kill a child of mine." Tragically, two of his grandchildren had already been aborted, when he saved the life of his next great-grandson with this statement. How can the "dream" survive if we murder the children? Every aborted baby is like a slave in the womb of his or her mother. The mother decides his or her fate. Q: What did you learn in your family about the dignity of human life? King: My uncle, Dr. King, said, "The Negro cannot win if he is willing to sacrifice the lives of his family for personal comfort and safety." My parents raised me as a Christian, and I believe the Bible. My grandfather, Daddy King, was very firm about the life of the unborn, and rejected the idea of abortion.

Wednesday, March 01, 2006

Walkin' the Dog by Walter Mosley

Walter Mosley's Walkin' the Dog is a continuation of the story of the 60-year-old Socrates Fortlow, the ec-convict who spent 27 years in jail for killing a friend and his friend's girlfriend, and has now been out of jail for 9 years, taking up his abode in a two-room shack in an alley in Watts. I listened to the book on CD, and the reading was highly differentiated and excellent. The first Fortlow story is Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned, which begins the exploration of Fortlow's attempts to find redemption for his crime through efforts that aid his community. This second Fortlow story is far more ambiguous in its plot, with the fight that Fortlow makes against his own rage and impulse to violence never an open and closed case, but a relentless fight. Provocations are plentiful.

Mosley names Fortlow Socrates because he often asks his friends to help him examine pertinent questions, and he also is part of a discussion group that meets each week. Because Fortlow is himself such an engaging character and also because he is in a search for the truth, about himself and his place in the world, this book in particular offers a glimpse into the inner thoughts of a man such as he.

He is a man, for sure, but it is not easy for him to take responsibility--not for his crime, which he did and does--but responsibility in relationships. For example, he gets a job at the Bounty supermarket quite a ways a way, and he is very responsible in this job, starting at the bottom rung, and the manager finds him to be the most reliable worker he has and offers Fortlow the post of Produce Manager, which would mean a big increase in pay and responsibililty to oversee a department. Fortlow is extremely reluctant to take this position, constantly offering arguments why he should not--including the argument of "What about the white guys that I will be supervising? They won't like it." [paraphrase] The manager says he doesn't care about that. Fortlow does take the job and does well, which would be expected.

He is also reluctant to take up the offer from Iula, who owns his favorite diner, that he combine with her and be her right-hand man in the diner. She wants to marry him, but he will not do this. She then goes back, briefly, with her former husband, and after they part, Fortlow takes her as his girlfriend, and they see each other on the weekends. Although Fortlow undoubtedly cares in some way and she certainly cares for him, it does not seem that he in any way emotionally gives up his fundamental independence or opens himself up to her in this relationship.

He takes moral responsibility for Darryl, the young boy he rescued in the first novel, although not physical responsibility for him. He teaches Darryl and also trusts Darryl completely. They confess to each other. It is through his relationship to Darryl that his aspirations for himself, both outwardly and inwardly, are mirrored for him.

Fortlow's major goals seem to be to defend his independence as a man against all forms of assault, from a mugger, from the police (who harass him constantly since he is an ex-con), from different kinds of women. He necessarily stands against hand-outs; he is reluctant to furnish his new apartment--"... his house was bare and pristine. He walked around the rooms smiling. He had a home that he loved but still he could disappear leaving nothing behind."

Socrates is trying to deal with his own anger, his own compulsion to violence. This is a physical feeling in him, like coming up his back and his neck into his hands, when it arises. At one point in his relations with the harassing cops, one of them is waiting for him at his gate when he gets home. The cop asks him where he has been, and Socrates answers,

"Nowhere, I ain't been nowhere. And I sure am tired so if you wanna arrest me please do it or let me pass." "Why would I want to arrest you, Socrates? Have you done something wrong?" Thats when Socrates realized that some time in the last week the violence had drained out of his hands. He didn't want to hurt anybody. He didn't care that Biggers [the cop] stood there in that silly suit trying to act like he was going to trick Socrates into a confession. A confession to anything. "Let me pass, man," was all Socrates had to say.

Later in the book, in his discussion group, Socrates poses this question: "What I wanna know is if you think that black people have a right to be mad at white folks or are we all just fulla shit an' don't have no excuse for the misery down here an' everywhere else?"

He then tells a story his aunt Bellandra had told him about a slave uprising in which the slaves kill the master and burn down the plantation and then head into the cane, from which they maraude other plantations but they can never leave the cane. The story is the answer to the question, the group says. "I'm not sure," Socrates said. "I mean I been thinkin' about bein' mad at white folks lately. I mean I'm always mad. But bein' mad don't help. Even if I say somethin' or get into a fight, I'm still mad when it's all over. One day I realized that I couldn't stop bein' mad. Bein' mad was like havin' an extra finger. I don't like it, everybody always make fun of it, but I cain't get rid of it. It's mine just like my blood." ... "Why did you ask the question?" Chip Lowe asked. "Because I'm tired of bein' mad, man. Tired. I see all these white people walkin' 'round and I'm pissed off just that they're there. And they don't care. They ain't worried. They thinkin' 'bout what they saw on TV last night. They thinkin' about some joke they heard. An' here I am 'bout to bust a gut."

Then, after everyone leaves, and he looks around the room and at his folding chairs and thinks of his friends who had been in in them [the group met at his house this night]. "He thought about being angry himself. Somewhere in the night he realized that it wasn't just white people that made him mad. He would be upset even if there weren't any white people."

Then in the last episode of the book, Fortlow decides to take matters into his own hands concerning a policeman who was known to mercilessly harass blacks and who had gunned down a teenage black boy for no reason at all. He bought guns and ammunition and prepared to kill the white cop, and stalked him for that purpose. "The murder in the air came in through his lungs and from there to his blood. Socrates, who knew that he had been prepared for centuries, was finally ready to answer a destiny older than the oldest man in the world. Cardwell [the cop] obliged and walked toward the dark alley. He was smoking a cigarette, moving at an unhurried pace. He was thinking about something. Socrates breathed deeply and tasted the air. It filled him with a sweetness of anticipation that he had not felt since the first time a woman, Netalie Brian, had helped him find his manhood.

'It was the air, no, no, no, the breath of air,' Socrates told Darryl the next morning on the phone. 'It was so good. I mean good, man. You know I almost called out loud. I saw Cardwell walkin' my way an' my hands was tight on them guns. You know he was a dead man an' didn't know it. .... But I was gonna murder that man. I was gonna kill him. But I was thinkin' that I had never felt nuthin' like that deep breath I just took. An' eve though I was gettin' ready to kill I had to take just one second to think about how I felt. You know?' ' I guess I do,' Darryl said. ' But how did you feel?' 'I felt free, ' Socrates said in a soft voice. 'All my life I ain't never felt like that. I was ready to die along with that man. My life for his--you cain't get more free than that." 'Did you kill him?' Darryl whispered the question... 'I meant to. The guns was out and he passed not three feet from me. But I just stood there--smiling, thinkin' 'bout how good it felt to be in my own skin.'"

Now this is a different kind of outcome than that prescribed by Frantz Fanon. According to Fanon, Fortlow could only have become free and found his own sense of identity by killing the cop. Instead, something about the air--or the air as encapsulating his talks with his friends and his relationship to Darryl and to Iulia and to others that he had been steadily building over the course of the two books--something in the air about his own reconciliation with others and with himself, made him choose life.

But he did not stop fighting. He then got a poster made listing Cardwell's crimes and picketed the police headquarters. This caused provocations on their side and then people gathered round to defend Fortlow from arrest and then there was violence by others, etc., teargas, etc., and Socrates in the news and famous with his billboard. He was jailed for 3 days and lost his job. He had no illusions that his act had fundamentally changed anything, but he felt good afterward and stayed in LA, it is implied, to continue his acts of self-redemption, to build his life with them.

Mosley names Fortlow Socrates because he often asks his friends to help him examine pertinent questions, and he also is part of a discussion group that meets each week. Because Fortlow is himself such an engaging character and also because he is in a search for the truth, about himself and his place in the world, this book in particular offers a glimpse into the inner thoughts of a man such as he.

He is a man, for sure, but it is not easy for him to take responsibility--not for his crime, which he did and does--but responsibility in relationships. For example, he gets a job at the Bounty supermarket quite a ways a way, and he is very responsible in this job, starting at the bottom rung, and the manager finds him to be the most reliable worker he has and offers Fortlow the post of Produce Manager, which would mean a big increase in pay and responsibililty to oversee a department. Fortlow is extremely reluctant to take this position, constantly offering arguments why he should not--including the argument of "What about the white guys that I will be supervising? They won't like it." [paraphrase] The manager says he doesn't care about that. Fortlow does take the job and does well, which would be expected.

He is also reluctant to take up the offer from Iula, who owns his favorite diner, that he combine with her and be her right-hand man in the diner. She wants to marry him, but he will not do this. She then goes back, briefly, with her former husband, and after they part, Fortlow takes her as his girlfriend, and they see each other on the weekends. Although Fortlow undoubtedly cares in some way and she certainly cares for him, it does not seem that he in any way emotionally gives up his fundamental independence or opens himself up to her in this relationship.

He takes moral responsibility for Darryl, the young boy he rescued in the first novel, although not physical responsibility for him. He teaches Darryl and also trusts Darryl completely. They confess to each other. It is through his relationship to Darryl that his aspirations for himself, both outwardly and inwardly, are mirrored for him.

Fortlow's major goals seem to be to defend his independence as a man against all forms of assault, from a mugger, from the police (who harass him constantly since he is an ex-con), from different kinds of women. He necessarily stands against hand-outs; he is reluctant to furnish his new apartment--"... his house was bare and pristine. He walked around the rooms smiling. He had a home that he loved but still he could disappear leaving nothing behind."

Socrates is trying to deal with his own anger, his own compulsion to violence. This is a physical feeling in him, like coming up his back and his neck into his hands, when it arises. At one point in his relations with the harassing cops, one of them is waiting for him at his gate when he gets home. The cop asks him where he has been, and Socrates answers,

"Nowhere, I ain't been nowhere. And I sure am tired so if you wanna arrest me please do it or let me pass." "Why would I want to arrest you, Socrates? Have you done something wrong?" Thats when Socrates realized that some time in the last week the violence had drained out of his hands. He didn't want to hurt anybody. He didn't care that Biggers [the cop] stood there in that silly suit trying to act like he was going to trick Socrates into a confession. A confession to anything. "Let me pass, man," was all Socrates had to say.

Later in the book, in his discussion group, Socrates poses this question: "What I wanna know is if you think that black people have a right to be mad at white folks or are we all just fulla shit an' don't have no excuse for the misery down here an' everywhere else?"

He then tells a story his aunt Bellandra had told him about a slave uprising in which the slaves kill the master and burn down the plantation and then head into the cane, from which they maraude other plantations but they can never leave the cane. The story is the answer to the question, the group says. "I'm not sure," Socrates said. "I mean I been thinkin' about bein' mad at white folks lately. I mean I'm always mad. But bein' mad don't help. Even if I say somethin' or get into a fight, I'm still mad when it's all over. One day I realized that I couldn't stop bein' mad. Bein' mad was like havin' an extra finger. I don't like it, everybody always make fun of it, but I cain't get rid of it. It's mine just like my blood." ... "Why did you ask the question?" Chip Lowe asked. "Because I'm tired of bein' mad, man. Tired. I see all these white people walkin' 'round and I'm pissed off just that they're there. And they don't care. They ain't worried. They thinkin' 'bout what they saw on TV last night. They thinkin' about some joke they heard. An' here I am 'bout to bust a gut."

Then, after everyone leaves, and he looks around the room and at his folding chairs and thinks of his friends who had been in in them [the group met at his house this night]. "He thought about being angry himself. Somewhere in the night he realized that it wasn't just white people that made him mad. He would be upset even if there weren't any white people."

Then in the last episode of the book, Fortlow decides to take matters into his own hands concerning a policeman who was known to mercilessly harass blacks and who had gunned down a teenage black boy for no reason at all. He bought guns and ammunition and prepared to kill the white cop, and stalked him for that purpose. "The murder in the air came in through his lungs and from there to his blood. Socrates, who knew that he had been prepared for centuries, was finally ready to answer a destiny older than the oldest man in the world. Cardwell [the cop] obliged and walked toward the dark alley. He was smoking a cigarette, moving at an unhurried pace. He was thinking about something. Socrates breathed deeply and tasted the air. It filled him with a sweetness of anticipation that he had not felt since the first time a woman, Netalie Brian, had helped him find his manhood.

'It was the air, no, no, no, the breath of air,' Socrates told Darryl the next morning on the phone. 'It was so good. I mean good, man. You know I almost called out loud. I saw Cardwell walkin' my way an' my hands was tight on them guns. You know he was a dead man an' didn't know it. .... But I was gonna murder that man. I was gonna kill him. But I was thinkin' that I had never felt nuthin' like that deep breath I just took. An' eve though I was gettin' ready to kill I had to take just one second to think about how I felt. You know?' ' I guess I do,' Darryl said. ' But how did you feel?' 'I felt free, ' Socrates said in a soft voice. 'All my life I ain't never felt like that. I was ready to die along with that man. My life for his--you cain't get more free than that." 'Did you kill him?' Darryl whispered the question... 'I meant to. The guns was out and he passed not three feet from me. But I just stood there--smiling, thinkin' 'bout how good it felt to be in my own skin.'"

Now this is a different kind of outcome than that prescribed by Frantz Fanon. According to Fanon, Fortlow could only have become free and found his own sense of identity by killing the cop. Instead, something about the air--or the air as encapsulating his talks with his friends and his relationship to Darryl and to Iulia and to others that he had been steadily building over the course of the two books--something in the air about his own reconciliation with others and with himself, made him choose life.

But he did not stop fighting. He then got a poster made listing Cardwell's crimes and picketed the police headquarters. This caused provocations on their side and then people gathered round to defend Fortlow from arrest and then there was violence by others, etc., teargas, etc., and Socrates in the news and famous with his billboard. He was jailed for 3 days and lost his job. He had no illusions that his act had fundamentally changed anything, but he felt good afterward and stayed in LA, it is implied, to continue his acts of self-redemption, to build his life with them.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)